Maier-Leibnitz, a gourmet physicist 👨🏻🍳

While I was reading Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s “Flow” (1990), I came across an interesting passage about a name I was certain I’ve seen before, Heinz Maier-Leibniz (1911-2000):

“Professor Heinz Maier-Leibnitz, a German experimental physicist, suffers from an occupational handicap common to academics: having to sit through endless, often boring, conferences. To alleviate this burden, he invented a private activity that provides just enough challenges for him not to be completely bored during a dull lecture, but is so automated that it leaves enough attention free so that if something interesting is being said, it will register his awareness. What he does is this: whenever a speaker begins to get tedious, he starts to tap his right thumb once, then the third finger of the right hand, then the index finger, then the fourth finger, then the third finger again, and then the little finger of the right hand. Then he moves to the left hand and taps the little finger, the middle finger, the fourth finger, the index, and the middle finger again, and ends with the thumb on the left hand. Then the right hand reverses the sequence of the tapping, followed by the reverse of the left hand’s sequence. It turns out that by introducing full and half stops at regular intervals, there are 888 combinations one can move through without repeating the same pattern “

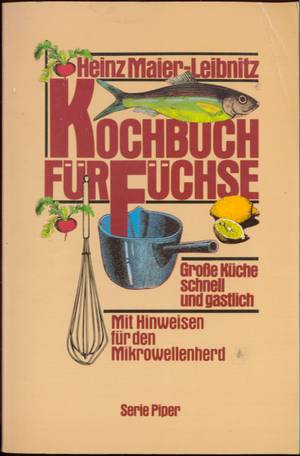

As I was trying to replicate his finger moves, I remembered that the nuclear physics lab in Garching, close to Munich, which I visited twice for experiments during my graduate studies, is named after him. I really enjoy reading about the history of science and lifes of scientists, so I started researching about him. After a while, I found that we share a common interest in cooking. Prof. Maier-Leibniz was a passionate chef and wrote three cookbooks, with the first, “Kochbuch für Füchse: Grosse Küche – schnell und gastlich” (The Crafty Cookbook Grande Cuisine - quick and homely) published in 1980. My cooking skills are definitely not in that level, but I love cooking, trying new recipes (there was plenty of time during the pandemic!) and of course tasting!

The cookbook was written in the early days of the microwave, and in it Prof. Maier-Leibnitz presents its added value to cooking in numerous places. For example, the water bath, that can be tiresome for desserts, can be replaced by the microwave. Prof. Maier-Leibnitz suggests to get a cheap appliance and vary the wattage using filled water glasses. After some search in the web, I managed to find one recipe from the book in a German blog. Unfortunately I don’t have a microwave to try the recipe but when I get one, I’ll definitely dive into!

Quark soufflé with rhubarb

for 4 people:

Ingredients

- 500 g rhubarb

- 250 g strawberries

- 150 g sugar

- 1 tablespoon lemon juice

- 3 eggs

- 1 teaspoon grated lemon peel

- 80 g low-fat quark (not to be confused with the subatomic particles!)

- 1 tablespoon cornstarch

- 1 tablespoon powered sugar

Preparation

Caramelize 70 g sugar, deglaze with lemon juice and 6 tablespoons water, add cleaned and cut rhubarb and let it steep for 5 minutes (in the pot or alternatively in the microwave). Butter 4 ovenproof ramekins (200 ml capacity) and sprinkle with sugar. Beat the egg yolks, 50 g sugar and lemon zest until very foamy and almost white. Stir in curd cheese and cornstarch. Beat egg whites with 30 g sugar until stiff and fold in. Cook for 20 minutes in the ramekins in a hot water bath at 180 degrees on the lowest rack. Alternatively, pour the mixture into the ramekins and cook at 360 watts for just under 2 minutes. Arrange on the compote and add the strawberries.

The mass rises very quickly in the microwave and collapses just as quickly, but it is fluffy-foamy in consistency, causes a very pleasant mouthfeel and is so quick to make that you can have it every day in no time on the table, if you cook the compote beforehand. You can use different types of fruit for a twist.

Gutes Gelingen! 😄

Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience by M. Csikszentmihaly

Neutrons for Science by B. Jacrot

Kochen mit der Mikrowelle – Die unterschätzte Antiquität by U. Thyll